I Beg To Differ

Of Souls and Star Babies: Cloud Atlas

Posted by Jennine Lanouette on Monday, November 26th, 2012

I have a lot of respect for Lana and Andy Wachowski and Tom Tykwer, the makers of Cloud Atlas. I believe they have a sincere desire to grace the world with art. They had a heartfelt message they wanted to communicate with this film and, judging from the $100 million budget, they intended for it to be heard by many, many people. Thus, I am sad that the film is not doing well.

This may sound odd, but I feel particularly sad for the German Film Fund that contributed something like a third of the budget. Knowing how badly the European film industry wants to be a player in the Hollywood game, I really wish they could have had a winner with this one. But it doesn’t look like they will.

This may sound odd, but I feel particularly sad for the German Film Fund that contributed something like a third of the budget. Knowing how badly the European film industry wants to be a player in the Hollywood game, I really wish they could have had a winner with this one. But it doesn’t look like they will.

It hardly needs pointing out that the project was ambitious. A non-linear, multi- story big budget event film? Hollywood kept at a distance, and it turns out wisely so. Knowing now that this is not an out-of-the-gate success, another question emerges: Will it build in stature over time? Will it go the way of films like Blade Runner and Brazil that were written off soon after their release only to later become classics? Or will it fade from consciousness in a few months?

From what I’ve heard, the novel on which the film is based was relatively linear by comparison, with one structural departure. The six stories follow one by one consecutively, each leaving off at a cliffhanger, until the last story is played out. Then the six stories follow again in reverse order, each coming to its resolution, with the novel ending at the resolution of the first story.

The filmmakers’ decision to have all six stories proceed in parallel is, in one way, more linear, since there is no reverse order to them, but, in another way, less, since the stories are all jumbled up together as opposed to the book’s tidy “nesting dolls” structure. In either case, the reader/viewer’s perception of linear time is being challenged, which serves the story’s theme of timeless interconnectedness between souls. The filmmakers simply chose a more dynamic structure for doing so, to serve the dynamic nature of their medium. It is easy to imagine how the book’s structure directly adapted to film would strain the patience of viewers. Even the more cinematic parallel structure seems to have strained the patience of many viewers.

The thing about non-linear, multi-story narrative is that it is not new. It has been creeping up on us for a few decades actually, and, with each new push away from conventional narrative, our perceptive faculties have managed to adapt.

Remember Annie Hall? When it came out in 1977, it was regarded as wildly disjointed in time. To look at it today, it seems like a comparatively straight path. Then came Pulp Fiction in 1994, adding multiple stories to the mix. But that was only three stories and Tarantino did no interweaving of them, instead sticking to something like an anthology structure. As for its non-linearity, it was really just one story shifted from the beginning to the end. With Traffic in 2000, the number of stories went up to a daring five, and were boldly interwoven. But Soderbergh was unsure enough about the viewer’s ability to stay oriented as he jumped from story to story that he gave each a different color scheme and shooting style.

So in Cloud Atlas we have not three, not five, but six stories to keep straight. And these six are not occurring simultaneously, as in Traffic, but across time. Neither are they time-shifted in one big chunk, as in Pulp Fiction, but in pieces. And they are not interwoven at a relaxed, grounding pace, as Soderbergh was careful to do, but tightly woven in dizzying succession.

I strongly believe in as-yet-undiscovered potentials of brain plasticity, not only on an individual level, where an injured brain can grow new neurons and shift brain functions from one region to another, but also on a collective level, where our perceptual capacity evolves as our external world presents more and more complex stimuli. Thus, in our enjoyment of film, with every new narrative innovation put in front of our eyes and ears, our collective 21st century brain readily adapts, and, indeed, seems to delight in the challenge, as we experienced when first encountering Annie Hall, Pulp Fiction and Traffic.

However, it’s one thing to bust out of old assumptions about what narrative must be, it’s another to actually move narrative forward an inch or two. In my last post, I carefully laid out the reasons why I think The Master, for all its busting out, doesn’t actually advance narrative practices significantly. What about Cloud Atlas? Is this a product designed for the 21st century brain that the audience hasn’t quite caught up with? Or, is the film an attempt to move things forward that, with time, will prove to be misguided?

It is my opinion that the filmmakers’ innovations in non-linear, multi-story structure are quite effective. The editing of the rapid transitions between time frames is rather breathtaking, with an organic sense of rhythm, pacing, momentum and a steady building of tension that never leaves the viewer feeling disoriented. The tight interweaving of the stories suggests simultaneity, which makes reference to both the quantum physics idea that time does not exist and the spiritual conceptions of a timeless ultimate reality and, thus, is in keeping with the themes of the film.

But I’m not sure that, therefore, the film, overall, is ahead of its time. There are other ways in which I find the film to be old fashioned. One is the lack of character depth. Each story’s main character has a generic feel, harkening back to the medieval Everyman. It could be the quick cutting made it more difficult for us to engage with these characters on a deep level. But I’m told the problem is also present in the book.

Another not-exactly-cutting-edge aspect is the filmmakers’ use of film genres. Each of the six stories fits neatly into a tried and true Hollywood category. The 1849 slave trade story is a Historical Drama. The 1936 persecuted composer story is a Tragic Romance. The 1973 corporate corruption story is an Action Thriller. The 2012 bumbling publisher story is an Absurdist Comedy. The 2144 oppressed automaton story is a Sci-Fi Actioner. And the 106 Years After the Fall journey to the mountaintop is a Sci-Fi Adventure.

On the one hand, this technique serves the film as a convenient way to differentiate the stories and therefore aid the rapid transitions. But I can’t help wondering if it’s also part of what has kept the mainstream audience away. Maybe this is the film that proves once and for all the old Hollywood dictum against mixing genres. All six stories add up to one big identity problem. The audience doesn’t know if they’re supposed to laugh or cry or perch on the edge of their seat. The problem I have with such faithful adherence to genre is that it makes the film visually conventional and at moments even a bit cartoonish.

But there’s another risk involved. Have you ever noticed how when film industry people talk about genre, they are talking about a specific genre under the assumption that all films fit into one genre or another? But when programmers and curators, those more oriented toward art film, talk about a “genre film” they just mean any commercial film? So maybe the wisdom here is not only to avoid mixing genres, but also to avoid mixing genre with an artistic intention (unless, of course, your name is Quentin Tarantino).

Speaking of Tarantino, there’s a filmmaker who used genre to revisit a collection of tried and true old story “chestnuts” with the express purpose of giving them a new spin. The result was a film about film form. There was no particular meaning intended in Pulp Fiction other than, “Look how far I can push the medium and you can still have a great time!” Nonetheless, the film is off the charts when it comes to interpretability, as reflected in the mountains of scholarly books, articles and dissertations devoted to decoding it.

But it doesn’t appear to me that Cloud Atlas was designed to elicit multiple interpretations. The intended meaning is rather explicitly stated, which is another way I find the film old fashioned. I can definitely get behind statements like, “Love is real,” “Separation is an illusion,” and “By each crime and every kindness, we birth our future.” But I could just as easily absorb these philosophical viewpoints by reading them in a book. A visual medium provides the opportunity to communicate another way, emotionally, into the unconscious. In my view, this is where the real cutting edge of film lies.

Not that a story has to be all uncommitted and interpretable to have unconscious impact. A definite point of view can do so just as well, as we saw in Traffic. The five interwoven stories each had a different outcome, but they were all in service to one overriding message: The drug war is a failure because drug addiction is a healthcare issue, not a criminal issue. While their multi-story structures may be similar, the notable difference between Cloud Atlas and Traffic is that, in Traffic, the intended message is never directly stated. Nonetheless, the meaning is unmistakable.

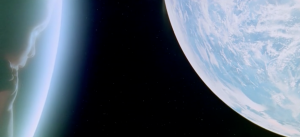

This is also why it surprises me when I read that, with Cloud Atlas, the Wachowskis wanted to make the next 2001: A Space Odyssey. In terms of film and storytelling techniques, the two couldn’t be further apart. To the degree that Cloud Atlas relies on dialogue, 2001 relies on visuals. Where Cloud Atlas has six stories, it could be argued that the Space Odyssey barely has one. Where Cloud Atlas is fast paced, 2001 is interminably slow. Not only does 2001 not speak its message through dialogue, it also uses a minimum of action.

But who can forget those visuals? The prehistoric apes, the black monolith, the bone wielded as a weapon, the circular space station, the upside down flight attendant, the red eye of HAL, the pod hurtling through space, the color bursts, the 17th century bedroom and the fetus floating in its amniotic sac. I wouldn’t dare try to articulate the meaning of the “star baby.” All I know is when it suddenly appears at the end of the film, glowing in its translucence and dwarfing the Earth in size, then slowly rotating until its gentle gaze seems to look directly at me, I am awe struck. The image lands somewhere deep in my unconscious, way beyond the verbal regions of my brain. And I am grateful to Stanley Kubrick for giving me that experience.

I have no doubt the Wachowskis hearts are in the right place. And I hope someday they will make a film to rival 2001. Or I hope somebody does. But for the time being, the film named for a future that is now in the past still holds reign as the most forward thinking instrument for exploring the mysteries of life beyond death.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

You can watch Cloud Atlas on the following Video On Demand websites: